When I was a child, I yearned for the mines. Flint and steel. This is a crafting table. Water bucket, release. Big old red ones.

Did that convince you to read this article? Were those references enticing enough for you? Let me try one more:

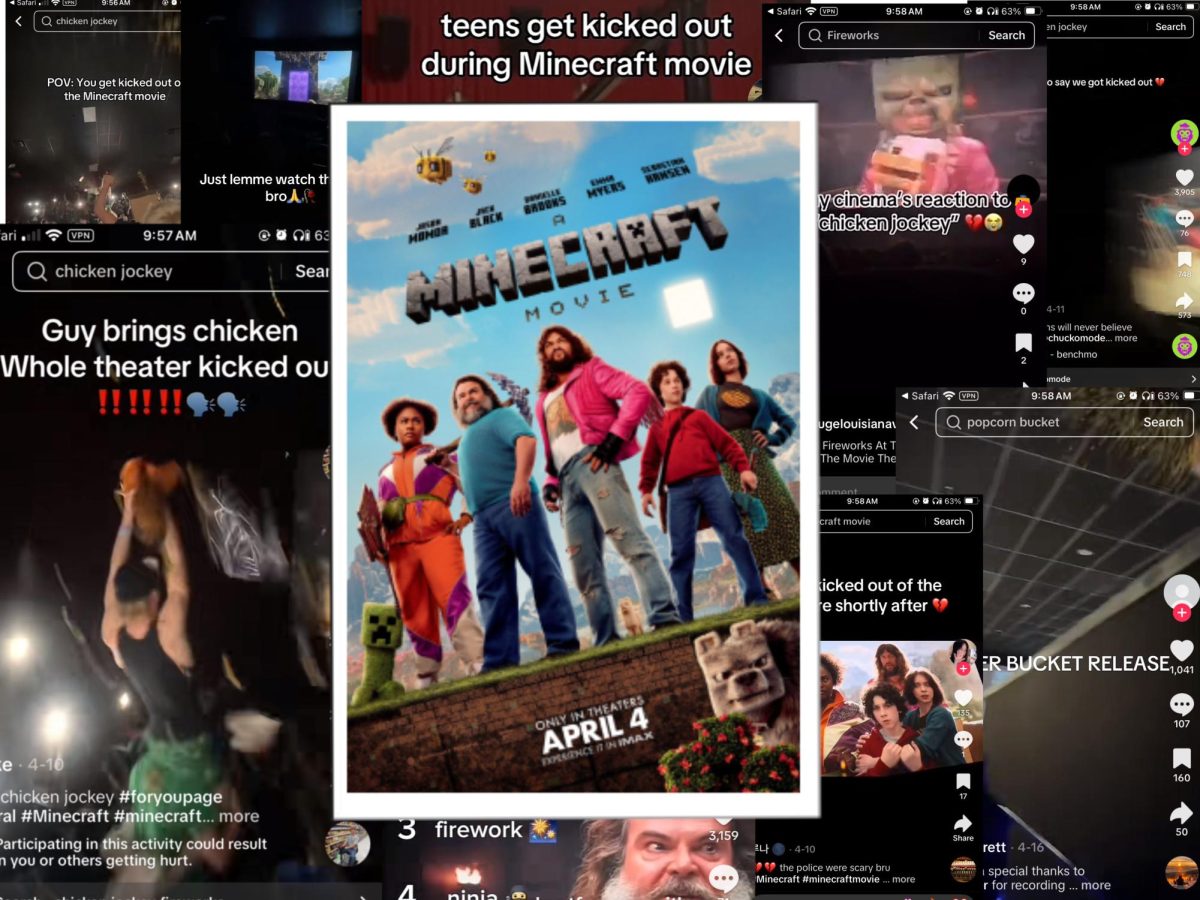

Chicken jockey.

The hype for A Minecraft Movie was immeasurable since its announcement in 2016. At the time, it was announced by Mojang, the studio that developed the video game, under the name Minecraft: The Movie. Disappointment ensued when the movie release was delayed to April 4, 2025. And that day has finally come.

The trailer of A Minecraft Movie was and still is a cultural phenomenon. Directed by Jared Hess, the movie was originally mocked for its strange casting choices, including Jason Momoa, Jack Black, Emma Meyers, Sebastian Hanson, and Jennifer Coolidge. However, the widespread hype for this movie grew exponentially because of the references to the game that were jam-packed into the trailer. The whole meme surrounding the movie felt somewhat forced to me. I consulted an online forum to see if anyone else felt the way I did, and found quite a few like-minded people.

Under a post with a link to a short form video that the movie’s marketing team released (which I can best describe as a 2012 YouTube slop meme), user MoncheroArrow said, “Honestly I don’t know how to feel about it, because I don’t think the execution is all that good and it just feels tryhard.”

Similarly, user anNPC said, “[I wouldn’t have liked this as a kid.] Any time a corpo slop company tried to relate to Gen Z when I was growing up we all thought it was abysmal.”

While I think the references, marketing styles, and overall promotional content are cheap ways to convince people to buy tickets to an otherwise less than decent movie, I have to admit that it worked. It worked so well. This film made $162,753,003 on opening weekend in the U.S. and Canada, making a profit on its estimated $150 million budget within days. And that number just keeps climbing.

Admittedly, I accounted for about $40 of that revenue. I won’t pretend that my cynicism of this movie made me immune to its charm. I saw it once on opening day with my brother, then again a week later with friends (and I did buy a crafting table popcorn bucket). My drive to see it came from quite a few different places. I wanted to write this article, first of all, and that would be hard to do without seeing the movie first. The second reason was nostalgia. I love Minecraft, and almost all people who have ever been important to me have Minecraft intertwined somewhere through their lore. The third reason was the fans.

At this point, it would be hard not to know what’s been happening at showings of this movie all across the country. People are throwing popcorn, trash, and drinks at the movie screens, bringing animals into the theater, screaming at any minor reference. This is, obviously, an awful time for anyone who does not enjoy popcorn rain, and especially those who have to clean up the mess. The worst part is that it is not usually children. The people posting videos of themselves and others doing these things look like teenagers, and should have more respect for their surroundings and for workers than they do.

I would argue that the only one of these actions that is mostly harmless is the yelling at references. In both of the shows I saw, the times when people yelled at references were the only times I really felt as though I was part of a larger community, and not just watching a bad film. This minor joy, however, does not excuse the abuse cinema workers have been through the last few weeks. At my second showing of the movie, I asked an AMC worker if our local Dartmouth theater was as bad as the others.

“Yes,” she replied, looking distraught and exhausted. “Everything you’re seeing on TikTok about it is true.”

Two weeks ago, when I first saw the movie, I would have told you that the crowd reaction was awesome. It was opening night, 10 pm in the Dartmouth Mall. Energy was very high in the AMC. The line to get concessions was nearly around the corner. All the workers were running around busily as people chatted among themselves, creating a hum in the air that felt nearly palpable. While watching the movie, almost every line had viewers in shambles. The crowd was cheering, dancing, booing, jumping, and laughing at every little thing. And honestly that was the best movie experience I have ever had.

It almost felt more like an improv show or a live performance rather than a movie, like the crowd’s reactions were more of the entertainment than the movie was. (Luckily, in that showing, no popcorn, drinks, or chickens were thrown at the screen.) Leaving that showing, I felt elated. The movie had far surpassed my expectations. It was corny, sure, but it was actually pretty fun to watch. It felt as though I had just connected with a group of people who all shared the same memories I did, who all came to see this movie for the same reason, brought together by our mutual love of blocks.

That feeling did not survive my second watch.

The second time I saw A Minecraft Movie was with three friends at 5 pm on a Friday. The theater was not as packed as before, and the air didn’t have the same buzz to it. People only cheered at two references.

That was when I realized that A Minecraft Movie is actually an awful film.

Why was the budget $150 million dollars if the movie was going to look that bad? Could the female characters have done a little bit more than build a hut that they sit in for five minutes? Seriously, why is the CGI so unsettling? What was up with that elytra scene? Why didn’t they make the child engineer do a single redstone build? I really cannot find an answer. Will someone please tell me why the backgrounds look so wrong?

Though I have heard similar sentiments on the Internet, there is a point to be made that it is just a kids’ movie, and does not need to be held to a gold standard of Sundance-level filmography. I am of the opinion that kids should be allowed to watch good media as well, and that this movie was not good media. There was no moral of the story, and the plot is half-baked at best. However, I do think this is a larger issue, and A Minecraft Movie focused more on references than content. I hope that the second movie (which is rumored to be in the works) will have a more substantial plot. As for this movie, a friend of mine, Hannah L., said after watching the movie for the first time, “That was terrible. I want to go see it 10 more times.”

Really, this movie is just the latest (and definitely not the last) installment in a long, ongoing trend of capitalizing off nostalgia—but A Minecraft Movie gets it so garishly wrong that it’s funny. The appeal of the game was mistaken for the culture surrounding it. The feeling of spawning in a new world, fresh and open for adventure, of finally moving out of a dirt hut into a real house, of taming your first dog, of the satisfaction of slaying the Ender Dragon after grinding for days, of laughing with your friends or family while you build houses next to one another, building your own small community to protect from the harsh outside world. That is the core of what has kept Minecraft alive for years. Not the bright flashy Lucky Block mods, not the Minecraft YouTubers who are adding just a little too much energy and action and stuff to their videos, not the merch and the Netflix interactive series and the constant game updates.

None of that is what keeps you coming back. It’s the pure emotion in the memory of your first time reading the end poem after beating the game.

and the universe said I love you

and the universe said you have played the game well

and the universe said everything you need is within you

and the universe said you are stronger than you know

and the universe said you are the daylight

and the universe said you are the night

and the universe said the darkness you fight is within you

and the universe said the light you seek is within you

and the universe said you are not alone

and the universe said you are not separate from every other thing

and the universe said you are the universe tasting itself, talking to itself, reading its own code

and the universe said I love you because you are love.

And the game was over and the player woke up from the dream. And the player began a new dream. And the player dreamed again, dreamed better. And the player was the universe. And the player was love.

You are the player.

Wake up. (Julian Gough, 2011)

Annica • May 3, 2025 at 2:48 pm

Learning that there’s a sequel in the works ALREADY made me sigh deeply. Excellent article, 10/10. Funny, passionate, and thought-provoking.