Pre-AP Programs Challenge Students and Teachers Alike

For English teacher Tara Kearney, many of her students had never heard of rhetorical analysis until they took her AP Language and Composition class as a junior or senior. Now, they’re learning it in the first weeks of their freshman year.

This is the result of the Pre-AP English program at DHS, which after several years of piloting, is mandatory for all freshmen. This eliminates English 9 CCR or Honors as freshman English classes.

The Pre-AP trend is expanding to other subjects as well. The Science Department is piloting Pre-AP Biology this year, and the Math Department is piloting Pre-AP Algebra 1 next year. Both biology and algebra 1 are foundational classes for freshmen.

In 2018, the College Board launched the first ever Pre-AP programs into 100 US schools. Now, thousands of high schools offer Pre-AP classes in 12 different courses. According to the College Board, the goal of Pre-AP is to “offer every student access to a high-quality education that prepares them for success in high school and beyond, including AP courses.” However, by implementing Pre-AP programs, DHS departments mainly want to establish academic homogeneity among the freshman class.

In 2022, DHS English Department head Will Higgins was reexamining the freshman English curriculum for a number of reasons. Namely, the department couldn’t guarantee that every incoming freshman was on the same page when it came to English Language Arts knowledge and skills.

As DHS continues to expand its school choice program, there are more students coming from other districts who have received different English Language Arts educations. This inconsistency is present among students who attended Dartmouth Middle School as well. Whether or not they know how to write an argumentative research paper, among other skills, depends on which eighth grade English teacher they had.

This discrepancy was aided and abetted by the ability of students to choose their course level. “Students would mostly select CCR or Honors based on social criteria,” Higgins said. A student might take CCR because they want to be with their friends, or Honors because their parents told them to. Their skill sets are not necessarily part of the decision.

“We found a lot of students coming in were not making good choices based on that,” Higgins said.

Additionally, Higgins wanted to add “sophistication and rigor” to the “static” English 9 curriculum. The program mainly focused on reading novels and analyzing their themes. It also lacked a formal writing curriculum.

All of these ambitions led Higgins to the Pre-AP program. The College Board offers two courses: Pre-AP English 1 and 2. After piloting both between 2022 and 2025, the English Department ultimately decided Pre-AP English 2 was a more rigorous course.

Higgins was satisfied with the pilot’s results. “The writing that was being produced by the freshmen was actually pretty impressive,” he said. “We hadn’t seen writing like that from freshmen in a long time. It seemed like it had definitely elevated what they were doing. You could tell that they were engaging with rigor, and they were using a lot of the concepts that were coming up.”

Rather than make Pre-AP English another level alongside CCR and Honors, Higgins decided “the right thing to do for equity” was to offer the class to all freshmen.

The Pre-AP English program is split into four quarters. The first and third cover content akin to that in AP English Language and Composition, while the second and fourth focus more on AP Literature-type material. Presentation and collaboration skills are sprinkled throughout, which play to AP Capstone skills.

However, the English department wanted to retain the core texts from their previous curriculum, such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Romeo and Juliet. In a sense, Pre-AP teachers are teaching two curriculums at once: the College Board work and the novels.

This has been especially difficult in the first quarter, where students are learning the nonfiction skill of rhetorical analysis while reading the fiction text To Kill a Mockingbird. To practice rhetorical analysis, the College Board provides articles about the disconnect caused by technology.

Some teachers, including Tara Kearney, Sarah Mitchell, and Wesley Lima, are trying to “blend” the two curriculums together. Rather than have students analyze the technology articles, Kearney gives them texts that better reflect the themes of To Kill a Mockingbird. For example, she has her students reading the article “Why White Parents Need to Talk to Their Kids About Racism” by Corey Silverberg; doing rhetorical analysis of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail; and conducting image analysis of Norman Rockwell’s painting The Problem We All Live With, which depicts Ruby Bridges of the Little Rock Nine walking to school.

“In my mind, if the students can do the same skills with a different piece that links to whatever we’re reading, it makes a little bit more sense,” Kearney said.

Other teachers, such as Jesse Grieve, are trying to teach the two curriculums simultaneously without changing materials. Oftentimes, she splits her classes in half, with the first dedicated to Pre-AP lessons and the second to To Kill a Mockingbird.

“The Pre-AP lessons are really scripted in the sense that we basically follow a guide to teach students the essence of the lesson,” said special education teacher John Breault, who co-teaches with Grieve. “That’s very much different than us creating what we would want to do, or adapting a unit to what we would want to do. So it is kind of rigid, but it’s also been helpful.”

Of course, since the Pre-AP program eliminates class levels, the freshman English classes are populated with a wide variety of students in terms of skill level. Some classes are co-taught to support students with IEPs and 504 plans. Breault noted that student skills are “holistically a little bit lower” this year. As a result, classes are moving through material at a slower pace as they navigate the tricky balance between making sure struggling students aren’t left behind and successful students aren’t held back.

“We hope that, in general, students will rise to that upper level if we continue to hold that bar higher than what they are used to,” Higgins said. “Then, over time, everybody will move in that direction. At the end, we don’t expect every student to be at an AP level. But we definitely expect that the students with low skill sets will be above what they were in previous years.”

The College Board makes it clear that Pre-AP classes are not Honors level classes. Wesley Lima appreciates the added rigor, no matter how substantial.

“I like being able to demand things from freshmen,” he said. “If freshman year English is too easy, they assume the next three years are going to be a joke. This is the opposite of that.”

Even though school has only been in session for two months, teachers are already seeing growth in students. Students are honing AP-level English skills, collaborating with each other to understand the material, and getting better at analyzing and understanding texts.

“I had kids laughing at To Kill a Mockingbird because they understood the language,” Lima said. “I find a lot of Harper Lee’s writing goes over their head, but we’re on Chapter 15 now, so they’re sort of accustomed to the language, and they’re laughing at the appropriate spots. They’re asking actual questions, too; they’re figuring out what they’re confused about and asking articulate questions, not just saying, ‘I don’t get it.’”

Higgins recognizes that his goal with Pre-AP is “lofty,” and that he’s asked his department to accomplish a large feat: completely rework the curriculum they’ve been teaching for many years.

“Some days teachers are probably clenching their fists as they walk out the door,” he said. “But I think there are other days, too, where it feels really good. It feels like we just did something we’ve never done before.”

The idea of creating a more streamlined and rigorous foundational class caught the ear of Arlyn Larson, head of the DHS Science Department.

Larson feels the department’s biology instruction is “beneath the ninth grade level.” On top of that, students select their desired class level arbitrarily, just as they do with English. Larson found that “precisely” 50% of incoming freshmen choose CCR, and the other 50% choose Honors. This results in “an unfair and a very imbalanced experience for all freshmen,” she said.

Biology teacher Dr. Peter Bangs said the levels end up “segregating” students based on academic history. CCR classes are mainly composed of less successful students, and Honors vice versa.

“In Honors classes, the students who would truly benefit from a real Honors-level push were getting it, but in CCR classes, the students who really needed to have some more aggressive learners in their class weren’t getting it,” he said. “It was a mess.”

In Dr. Bangs’s experience, CCR classes discourage upward academic mobility. “I think that we have very, very few kids in our historic CCR-level classes who take the AP level classes,” he said. “I don’t think they feel that they get the preparation, and to be honest, they haven’t.”

The Science Department is currently piloting two sections of Pre-AP Biology, both co-taught by Larson and Dr. Bangs. Next year, however, Pre-AP Biology will be mandatory for all freshmen.

The course content isn’t different from the CCR/Honors curriculum—it’s still biology, occasionally adapted to better align with State of Massachusetts’s standards. The difference is the approach to learning.

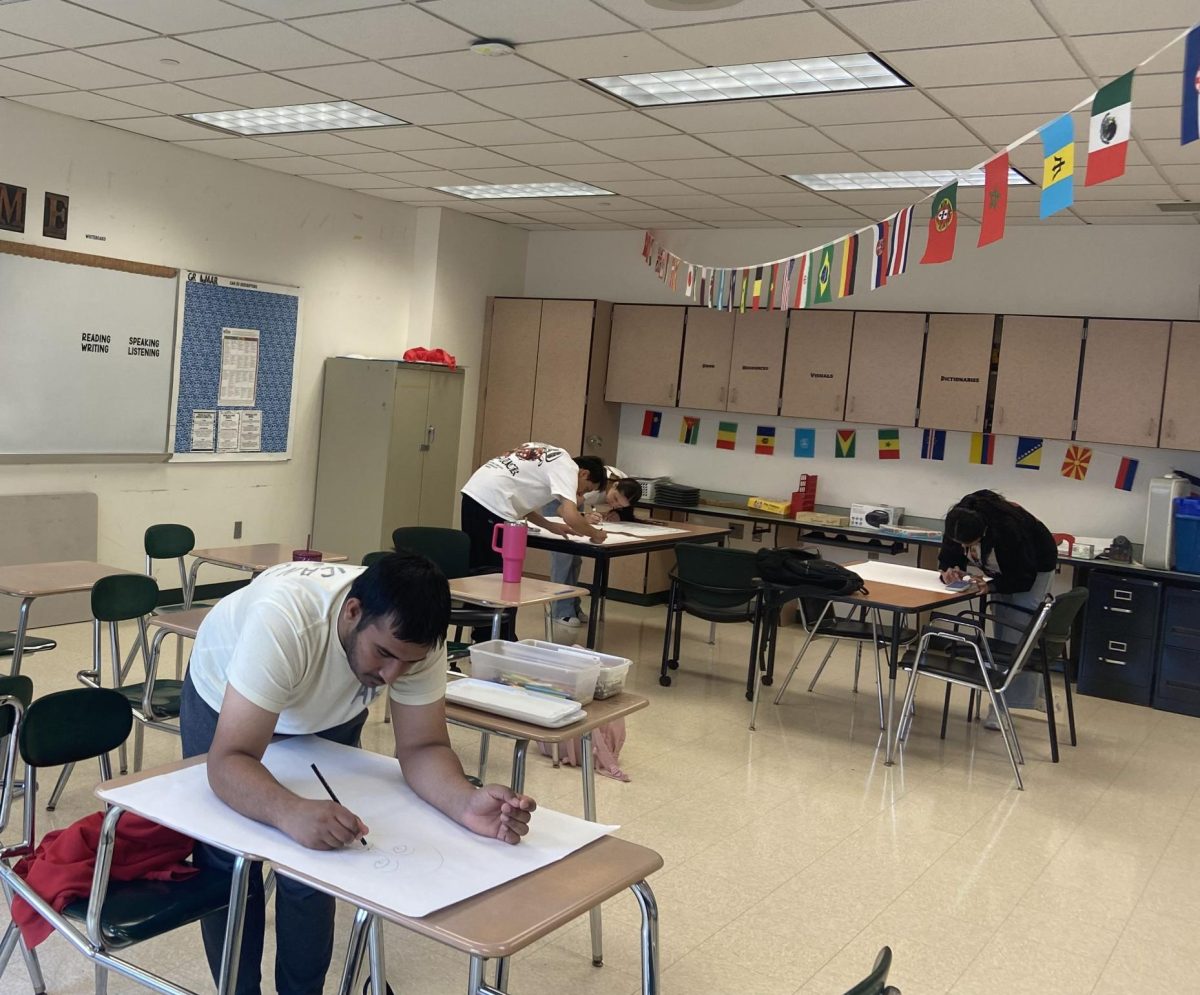

The student-centered course prioritizes teaching skills over content, specifically academic dialogue, analytical reading and writing, strategic use of math and modeling, and critical thinking. When they walk into class, students no longer sit down for a long lecture. They’re given a reading about the topic of the day. Then, they discuss the reading in groups and use their newfound knowledge to work through an activity. From there, they revise their work based on peer critique. Only after the revision process does the teacher launch into direct instruction, to fill in any gaps and ensure the students took away what they were supposed to learn.

Although some students are “rather appalled” at the level of engagement this new format demands of them, Dr. Bangs said, he has seen participation increase across the board, regardless of student skill level.

“That was not what we observed often, particularly in the CCR level class,” he said. “We had so many kids in those classes who were used to not being successful and used to not trying because they never felt that they would be successful. And so you had these learning environments that were not very healthy.”

By implementing Pre-AP Biology, the Science Department isn’t necessarily aiming to have more students take AP classes. However, the emphasis on application rather than memorization better prepares students for AP Biology, where “there’s no regurgitation at all,” Larson said.

“Students are never going to be asked, ‘What does osmosis mean?’ They’re always going to be presented with a scenario that they’ve never heard of before, and they’re expected to predict an outcome based on what they know about osmosis,” she said. “That’s very much true of Pre-AP as well. We’re not interested in your answers; we’re interested in your thinking.”

As with their colleagues in the English Department, pace has been a challenge for Larson and Dr. Bangs. It’s taken them a long time to move through the material, and they’ve already identified topics that they will tighten up next year.

Larson attributes the slow speed to two factors: the “depth” required of students to master each topic, and the inherent challenge of teaching a new course for the first time.

“We’re building the plane while flying,” Larson said, a phrase echoed by several English teachers. “Now that we’re done with cycles and we’ve moved into food webs and food chains, the content naturally lends itself to speed. But again, who knows what the next unit will hold?”

For one section of Pre-AP Biology, Larson is the primary teacher and Bangs is the co-teacher; they swap roles for the second section. This dynamic allows them to play off—and take inspiration from—each other’s unique teaching styles.

Larson knows Dr. Bangs is “very, very comfortable” putting students in charge of their own learning, whereas she prefers direct instruction. “He’s not afraid of the mess,” she said. “He’s encouraging students to learn from their mistakes, and that’s the nature of the class. Learning from your mistakes is where the true learning takes place.”

Dr. Bangs believes he and Larson are “very excited” to teach Pre-AP Biology again with a year’s worth of experience behind them, as they know they “can do this better and make the kids work even harder.” They’ll also be better equipped to advise other biology teachers who will have to teach Pre-AP—and it will be a completely new team, as Scot Boudria, Dorann Cohen, and Renee Vieira are retiring this year.

The idea that any student had the option to take an Honors level class promised equity, but, in Dr. Bangs’ view, failed to do so. “Now, every student has the same opportunity in reality, not just on paper,” he said. “That, to me, is most important, regardless of the Pre-AP approach to anything. We’re going to have better readers who are critical thinkers and communicators. Whether or not they’re brilliant in biology content knowledge is not the point. They can apply all those skills to all of their classes, and I think that’s going to give them more confidence to take higher level classes, not just in science.”

“So I am determined to make this work, and I know Mrs. Larson is determined to make this work, this year and moving forward,” he concluded. “This is the way it needs to be done.”