Finn Sperry wants to win another national championship. When the Dartmouth sailor and his longtime teammate, Peter Herlihy of Tabor Academy, entered the C420 National Championships at Little Egg Harbor Yacht Club in New Jersey last summer, they saw themselves as underdogs. But they left as champions.

So how did the duo manage to outperform 128 other boats? Spoken like a true athlete, Sperry reaches past the years of experience he’s built up and chiefly credits his triumphs to his state of mind going into the competition. “When you start racing or competing at the highest level, it’s 90 percent psychological,” he said. “You know how to do everything, you just need to make sure you are doing everything—it’s super mental.”

A small-boat racing team consists of a skipper and crew. At its absolute core, the crew’s job in a C420 is straightforward; trim the jib (the smaller sail) and distribute your weight; the skipper steers and manages the main (larger) sail. However, as with any sport, an athlete’s skills become more intricate as the level of competition rises. Monitoring the wind for even the tiniest shifts in direction or speed becomes an instinct for elite racers such as Sperry. Competitive sailors need a strong combination of technical skills, tactical awareness, and focus, along with physical conditioning and an automatic understanding of the rules of racing and how the boat responds to wind, current, and waves. It also involves keeping mentally in tune with your teammate. For Sperry, crewing with Herlihy is a balancing act. “A big part of my job as a crew is the mental side and keeping Peter happy,” he said, “because if he’s not happy, then we don’t race well.”

As the steep waves created drag and slowed down the other boats, Sperry and Herlihy took advantage and kept surfing over the waves, breezing past the competition one boat at a time.

“We would just constantly keep the race progressing,” he added. “You need to keep a constant flow, so you don’t get bogged down by little mistakes.”

The years Sperry and Herlihy have spent sailing in Buzzards Bay conditions is what Sperry views as the factor that gave the two an edge over the rest of the fleet in New Jersey. Within the barrier islands off the Jersey Shore, where the nationals meet was located, weather conditions were similar to those he and Herlihy had grown up sailing in, Sperry explained.

Steep, long waves gave the team the opportunity to capitalize on the downwinds, the team’s strength. “That’s our whole thing—[sailing] downwind and surfing. We passed 20 boats on every downwind [leg].” Using the speed they gained from sailing the downwind legs then helped them to overtake other boats, he explained: “The waves were super steep on the upwind, so you had to be able to plane over the waves without taking them over the bow and filling up with water. We could do all that because we were used to it.”

“If it were different conditions we probably wouldn’t have won, so we kind of got lucky,” Sperry admitted, “but I’ll take it.”

Another element of the mentality that the pair carries with them into competition is a conscious effort to divert their attention away from the race results. Obsessing over their finishes and standings after every race doesn’t allow them to stay present and focused. They restrict themselves to only checking results after a given regatta is completed. However, in the case of nationals, Sperry and Herlihy had their suspicions about how well they had performed. “We didn’t actually know that we had won,” he recalls of the national championship. “Our coach came up to us and asked, ‘How does it feel to win your first regatta?’”

Their summer coach, Zoë Hoctor, is senior captain of St. Mary’s College of Maryland’s well-regarded sailing team. With Hoctor as head race coach for the New Bedford Yacht Club, Sperry says the whole NBYC race team became one big family. “She’s like my adopted sister now,” he said.

Sperry has two siblings: his identical twin Sam and their older sister Maisy. Like Sperry, they both became heavily involved in the NBYC race team and DHS’s sailing team. Maisy graduated from DHS in 2024.

Finn and Sam began sailing at the New Bedford Yacht Club at about age eight, then started racing at 11. It’s fair to say that sailing is in their blood. “My dad sailed around the world and wrote a book about it. I wouldn’t be into sailing if it wasn’t for him.” Maisy started sailing in 2019 after Finn and Sam did. She is currently studying abroad at sea, which is also something Finn potentially is interested in doing as well.

Like many sets of twins, the Sperry brothers are both close and competitive with each other. For a long time, they sailed against each other. In fact, they didn’t start racing together until recently, when they competed in a January regatta in Jensen Beach, Florida after practicing together for just three days.

“Sam and I didn’t sail together for the longest time. We were just constantly pushing each other, and that goes for pretty much everything that we do. Now that we’re sailing together, we had to put our rivalry to the side, and it’s worked out pretty well. We got sixth overall out of about 180 boats [in Jensen Beach] and we were total underdogs.”

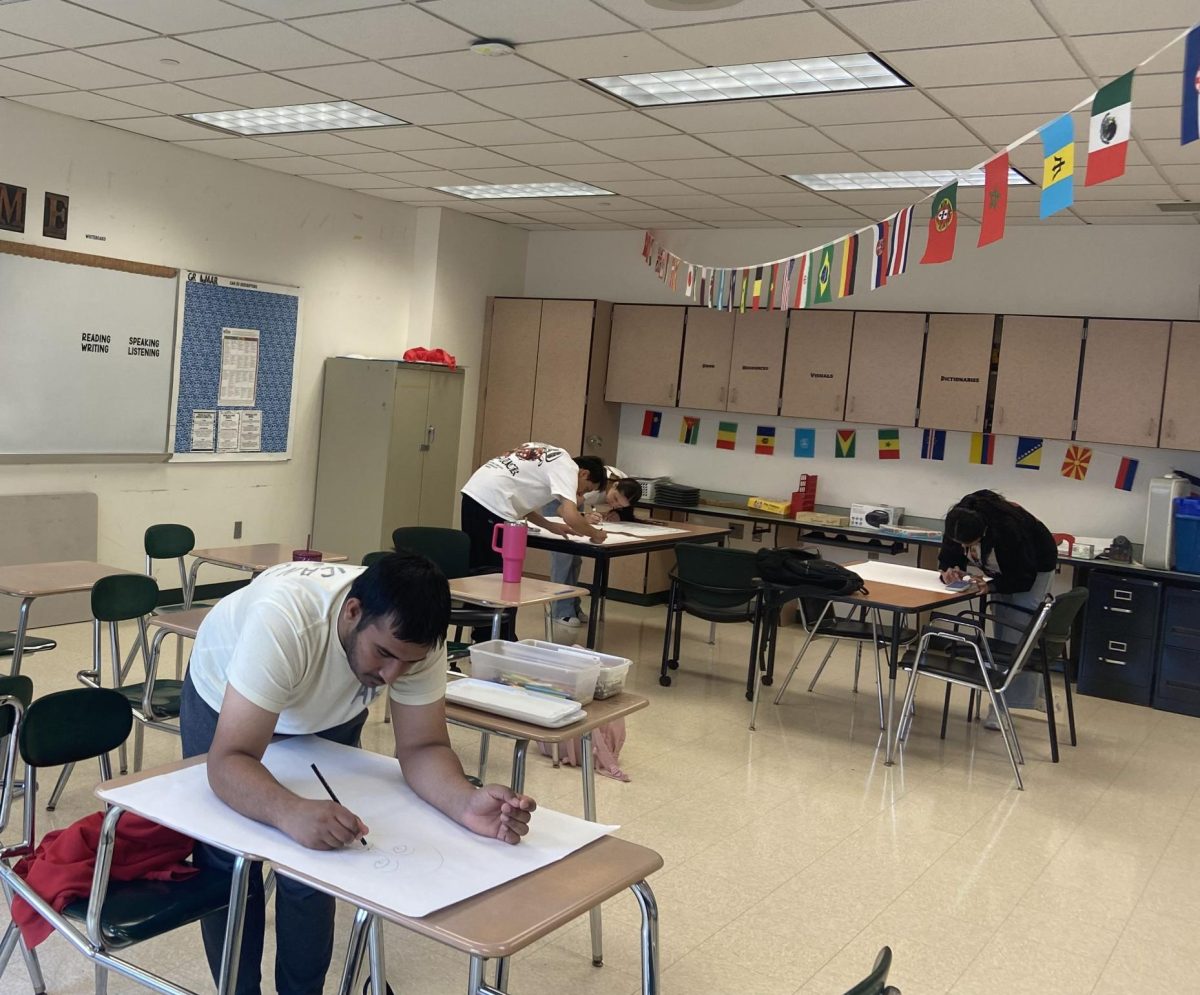

Apart from being identical twins, what sets Finn and Sam apart from other sailing duos is their lack of connection to a private team. These teams are costly and pull out all the stops (and empty their pockets) to give their sailors the best resources possible. They travel all across the country competing in national events and use elaborate equipment to collect data about racing conditions. “They’ll have buoys in the water measuring current, drones up above measuring wind—they’re super intense,” Sperry explained.

This July, Sperry hopes to repeat last summer’s triumph. The 2025 location of Nationals is Hyannis Yacht Club, giving the Dartmouth native a home field advantage. This year will also see the graduation of a class of talented sailors, allowing younger ones to vie for the Cup while also lightening the competition. Sperry has never placed below top-10 in a national sailing competition—events that typically have between 100 and 180 boats vying for the finish line.