Eyewitness to History: A Moving Portrait of Hope

Yours truly asks Souza what advice he has for young people who want to document history as journalists or photographers. Citing advice he stole from NPR, Souza says to write a page or take a photograph everyday, as well as seek authentic constructive criticism from people who aren’t your friends and family.

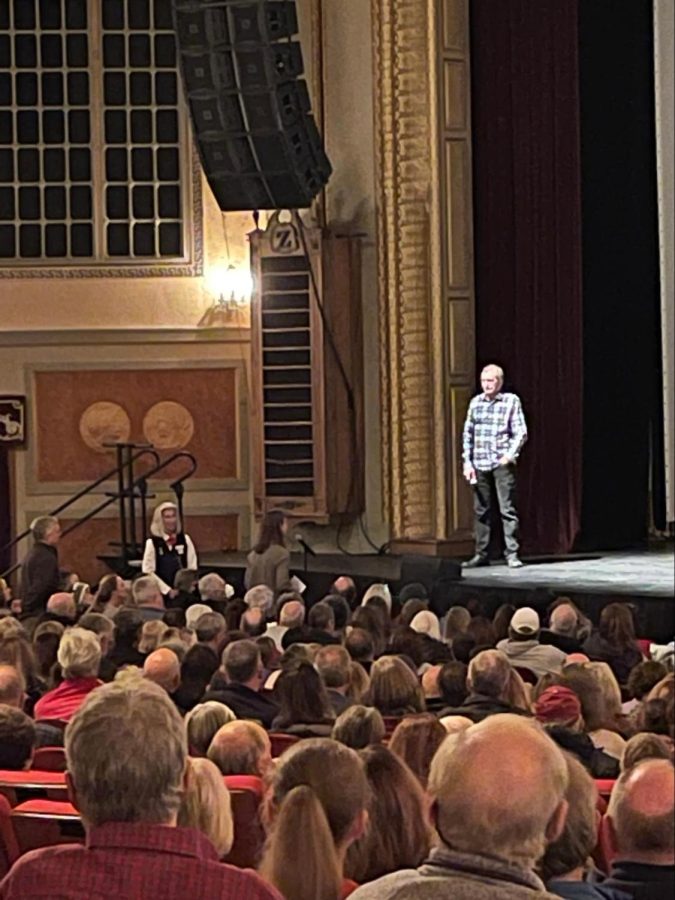

There hasn’t been a president from Dartmouth – yet. The closest our town has ever gotten to the White House is with Dartmouth High graduate Pete Souza, a photojournalist famous for capturing President Obama’s two terms. The Spectrum’s former Editor-in-Chief Mary Bancroft covered his fascinating journey in 2018, following the release of his book Obama: An Intimate Portrait. With his new book The West Wing and Beyond: What I Saw Inside the Presidency, Souza stopped by the Zeiterion Theatre on December 8, 2022 to present Eyewitness to History, detailing his experience as a photographer.

There’s a humbleness to Souza’s demeanor. Wearing a plaid shirt, he gave his presentation from a podium off to the side. A simple black PowerPoint in Arial font served as the bumper for his photographs. He has a slow and gentle voice that lilts when he cracks a joke.

He began his story when he was in fourth grade, 1963. The day after the assassination of President Kennedy, the front page of The Standard-Times featured the famous photograph of Lyndon B. Johnson taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One. Souza cut out the photo and taped it on his dresser. It was when he first became enthralled by the power of the still photograph.

Souza proceeded to take his camera to Kansas, then Chicago, and eventually the White House in 1981 when he became the presidential photographer for Ronald Reagan. That role provided him with the knowledge of presidential life and the most effective way to chronicle it.

After Reagan left office, Souza worked for The Chicago Tribune, where he met Barack Obama after reporting on the war in Afghanistan from Kabul. Rumors about presidential runs were just beginning to swirl around the young senator as Souza saw him crammed in a small office, attempting to eat some lunch as his daughters stopped by to visit. The humanity and modesty of those first photographs would set the precedent for his portrait of Obama.

The president granted Souza full access to the White House, so the photographer was in every meeting, ceremony, speech, motorcade, airplane. He purchased two cameras that were as quiet as possible. “I was unobtrusive,” he explained. “I became a part of the presidency. People got used to me being around.”

Souza’s omnipresence allowed him to capture President Obama from many different emotional angles. Different sections of the presentation read “President.” “Husband and Father.” “Humanity, decency.” “The Best Day” – the passing of the Affordable Healthcare Act. “The Worst Day” – the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting. Souza brought the audience from the tension in the Situation Room during the bin Laden raid to the joy of the president and his daughters making snow angels in the 2010 blizzard; from the solemnity of Cabinet meetings discussing the financial crisis to staffers holding up miniature basketball hoops so the president could take a shot. There were many sobering moments as Souza recounted the pains that struck America throughout the recent decades, but there were several hilarious stories that encapsulated President Obama’s joking behavior and the introspective absurdity of the highest office in the land.

A common theme throughout the presentation was young people. Dozens of photographs featured toddlers visiting the president in Halloween costumes, or teenagers crying with hope during the youth inaugural ball. Souza would name a child in each photo and follow up on where they were now; many were pursuing political careers and on their way to Washington.

Garnering huge laughs with unnamed snipes at Obama’s successor, Souza finally identified President Trump by name when covering the meeting between the outgoing and incoming in the Oval Office. He didn’t linger on it long, instead contrasting it to the meeting Obama had right after with a six-year-old boy named Alex.

Alex wrote a letter to the president asking to bring a young boy brutally injured in Syria to his home. “We will give him a family and he will be our brother,” the letter reads. “Please tell him that his brother will be Alex who is a very kind boy, just like him. Since he won’t bring toys and doesn’t have toys [my sister] Catherine will share her big blue stripy white bunny. And I will share my bike and I will teach him how to ride it. I will teach him addition and subtraction in math.”

When asked by an audience member which upcoming politician he saw as the next Obama, Souza answered that he didn’t know any well enough to make a decision. But Souza used the presentation to display the beauty in Obama’s compassion and paralleled youth as the ones who will carry on his ideals.

His final words to the audience were, “It is this generation that will keep hope alive.”