Every teacher teaches differently, coinciding with personality and education, and having experience with diverse teaching styles is valuable for students, but what about different grading policies?

There is no uniform standard to weigh classwork, summative, and formative assessments at DHS, making it not only difficult to navigate for the average student, but for colleges as well. If you have some teachers whose tests count for 70% of the overall grade, and others where it is only 40%, the value of tests as a whole is shrouded, and it is not easily seen where students should maximize their effort.

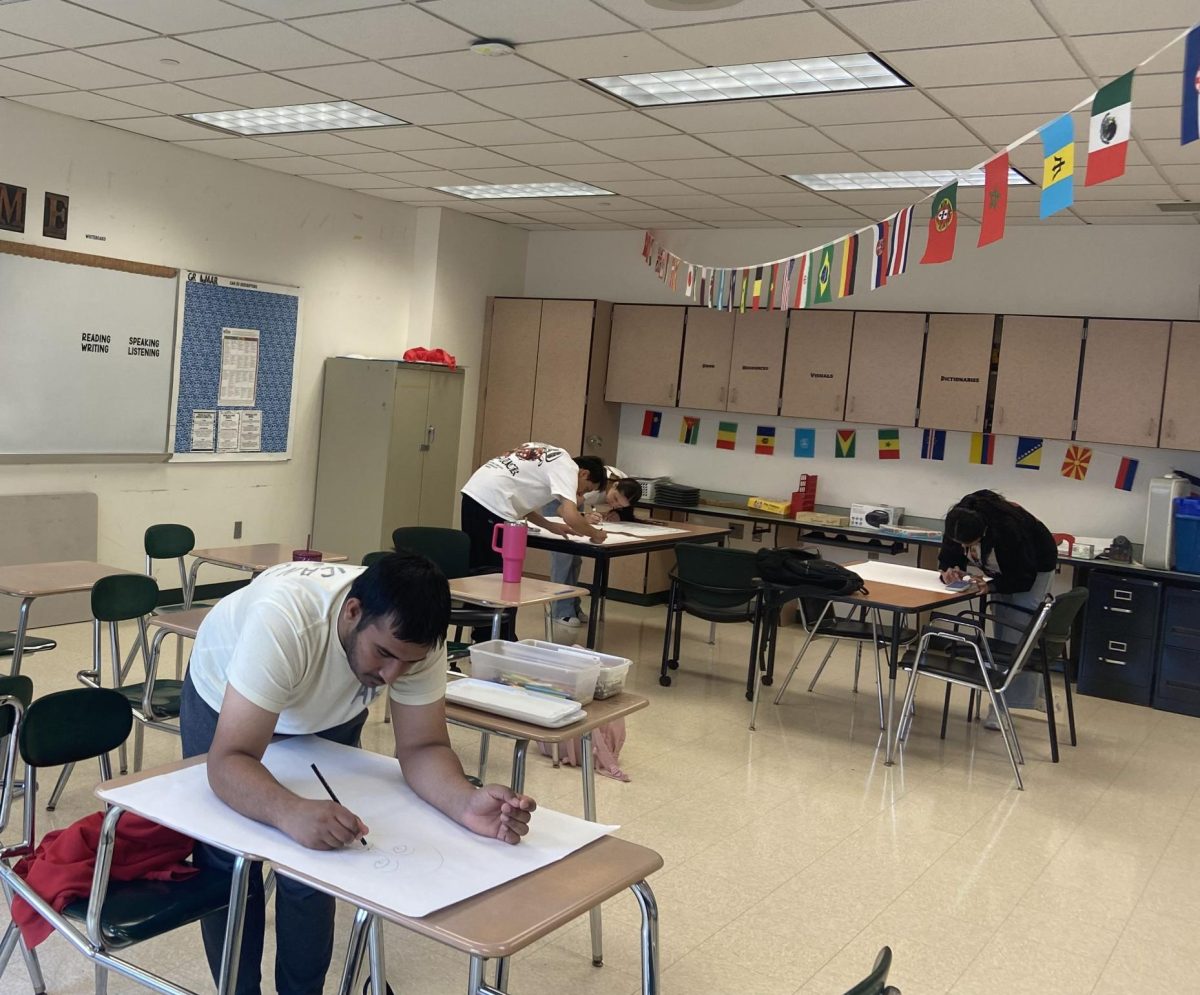

Several recent DHS Faculty meetings have revolved around readings and discussions of equity and fairness in grading, and there appears to be a movement toward some version of a uniform grading policy.

The Spectrum sought out a number of teacher perspectives as part of a series of articles centered around this grading issue. Teachers voiced concerns about retakes and uniformity, as well as how much time grading consumes for many of them.

When asked about the current faculty conversation around grading policies, Portuguese Teacher Nathan Carvalho said, “I think too many people are trying to reinvent the wheel and are using grading for the wrong reasons.”

Science Teacher Scot Boudria said, “To say only one way works I think is wrong. I also understand how parents, administration and students also want a fair way among different teachers, so again there’s both sides to the argument and neither side is wrong.”

The general consensus among the several teachers interviewed across departments is that there is not enough time to grade, but how to fix this is unclear.

Science Teacher Dr. Peter Bangs said, “I think it’s important that students get feedback quickly on what they did. That’s the whole point. It annoys me to know that students are doing the work, and they don’t even learn how they did for weeks. What is the point of giving the assignment if they’re not learning from it? How do they learn from it if they don’t get some feedback on it?”

Part of the faculty conversation appears to be about the possibilities for a schoolwide grading policy, and of course, there are varying opinions.

Science Teacher Matthew Tweedie said departments should have the same grading system, but that one uniform way across the departments wouldn’t work. This is especially important for science where labs can count as an entire grading category.

Dr. Bangs explained, “As a science teacher, we also have a laboratory component that’s generally 25% of your grade. In my view, you don’t really learn science without doing science. But you can’t make it too high, because oftentimes students work together on their lab reports – which is good, I encourage that – but then I can’t really tell if both lab partners know exactly what they’re doing.”

Another component of the over-boiled soup that is DHS grading is the inconsistent retake policy. On the one hand, you have some CCR teachers who deny any retakes, and on the other you have AP teachers who may allow for retakes up to 100% and vice versa.

Mr. Boudria expressed concern that “many kids take advantage of retakes by looking at old tests.”

Retakes can be viewed as a second chance for those who genuinely had a bad test day, or a second chance to cheat the system with more time to study.

The teachers interviewed all agreed that there should be retakes offered to an extent, but that extent is as different as each teacher.

Social Studies Lead Teacher Jeff Reed said, “I’m in favor of it with parameters; they shouldn’t be unlimited. Students should have to prove they deserve the retake. It’s a safety net. I’m not in favor of it for students who have a 96% who want an A+.”

On the other hand, Mr. Carvalho said, “I definitely believe in second chances, and if any teacher in this building ever says they never had a second chance, they are lying. However, a second chance is earned, not given.”

To combat the fear of unnecessary retakes, it is commonplace to only offer a retake if a student fails, and sometimes only allow them to retake up to a 70%. This, however, can be seen as a second chance that can only minimally save a student’s grade, for if you only have 2-3 tests a quarter, and tests count for a majority of your grade, one 70% can have an outsized effect.

English Department Will Higgins recalled that during a recent faculty meeting, when teachers were given the same student profile with the same classwork and test grades, and asked to calculate the final grade, the end results varied from Ds to high Bs depending how the grade was calculated according to the teachers’ present grading policies.

This is concerning given that in theory this means a student can give the same amount of effort in each class, yet yield wildly different results.

Faculty discussion of DHS grading policy is on the top of the docket right now, and if one thing has been made clear, every teacher seems to have a different outlook, as well as great hesitation for adopting any one uniform policy.

Ahmed R • May 28, 2024 at 10:17 am

Teacher opinion seems to really reflect on their grading policy

Standardization would be nice, If rivard is the normal unmodified late policy, then the late policy could stand to be nicer