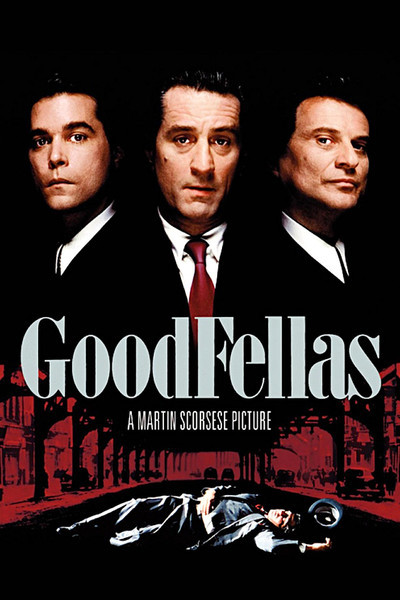

Scorcese’s GoodFellas: The best mob film ever made?

GoodFellas is quite possibly one of the greatest films of all time. Its spot at the top is well warranted, maybe even irrefutable in terms of scale and importance. Martin Scorsese excels in harsh realities both historically and culturally in the real-life mafia movie aficionado. Paired with performances and a presentation that propel the accuracies to a dramatic, cinematic, and powerful height, the film’s ethos is well established.

GoodFellas still stands uncontested by any other crime drama as one of my favorite films of all time (right next to The Dark Knight). GoodFellas is the quintessential mafia movie and a masterwork of cinema due to a multitude of factors.

Sure, I could discuss the sublime cinematography, the phenomenal soundtrack, the dynamic performances, the profound visuals, or the immensely satisfying narrative, but one asset often not appreciated enough oddly, is the historical prowess. In comparison to other films of its caliber, this makes GoodFellas a “real” masterwork.

To clarify, I value the realism and accuracy portrayed in this flick due to how it complements and supplements the product to begin with. The very notion that a film must be “realistic” to be any good or even relatable is dismissive and reductive.

Such a way of thinking certainly doesn’t work in the case of Mario Puzo’s Godfather, one of the greatest American films of all time that some would put above the likes of GoodFellas. And while I myself won’t weigh in on the debate, (though my stance should be obvious), I must say that I still adore the Godfather and its sequel to bits. But the greatness of GoodFellas, highlighted by all of the strengths mentioned, shines brightest in respect to its real-life counterparts and historical grounding depicted so faithfully here.

Many people are unaware of it being based on a true story. Real shame, as GoodFellas is so much more than just a crime drama rife with iconic performances, a great soundtrack, and novel camera tricks. GoodFellas is an objective and brutal look at the mafia, being simple yet definitive. It never once strays from showing the visceral violence and gritty actions of these mobsters. These men were psychopaths, not gentlemen; monsters with no moral code of honor or respect.

This is the fundamental core of a gangster or mafia movie; whether you go the Godfather route of romanticizing and sugar-coating the mob’s fame, or the GoodFellas route, where you present the belligerent realities and unkempt truths that bolster its infamy.

GoodFellas has many tricks up its fitted-suit sleeve, including the aforementioned dramatic, dynamic, and lusty performances. Many stand out, the obvious being the main cast. Unsurprisingly, their performances are consistent with their real-life counterparts. Henry Hill, portrayed by Ray Liotta, is so much like the living-legend of a man and former mobster by the same name, it’s actually uncanny.

Joe Pesci’s character, Tommy Devito (while looking nothing like Tommy DeSimone), in the “What do you mean I’m funny?” scene also expertly captures the dangerous, temperamental, and psychopathic nature of these men.

This spot-on casting continues with Tommy, in (Oscar-worthy) particularity, as a cowboy with a big mouth and a big chest, despite his stature and size.

The masterful addition of Robert De Niro as Jimmy Conway (a name changed from the real man, James Burke, due to his still being in prison at the time) holds the entire cast and production together, acting as the vital luster and charming glue of the film.

All in the first act, the fruits of Scorsese’s (director) and Ballhaus’s (cinematographer) labor are made deliciously clear. The systematic Mafia-member post-whack montage played over a cheery, yet pathos-driven “Layla” (the piano exit) by Eric Clapton, scratches the surface of excellence and the middle-mark.

Then there’s Billy Batts’s very own (attempted) whacking scene, which is feverishly exciting and satisfying, in a sickening, guilty helping of made-man stomping, pistol-whipping, and disparaging shoe-shining, all coated in the angelic and hypnotic “Atlantis” by Donovan.

The kill after this bar-battery actually resides within the iconic opening scene of a profusely gritty (indicative of the film) final kill of a battered and bloody Billy Batts, with a car closing and cued roar of “Rags to Riches” by Tony Bennett showing off charisma and excitement in spades, setting the scene and a generation of film with it, right in the intro.

The Mafia’s dinner get-together, where Scorsese introduces us to every member of the gang in one continuous shot, the topper shot of Tommy shooting the camera, pays homage to The Great Train Robbery in a terrific callback and a fun nod of a send-off.

Even when not discussing the fully essential, or high praise of the first act (I swear that’s where 80% of it resides), the climax and conclusion are intelligent and intrepid. The brutal and snappy cuts in the final act in portrayal of the escapading chase and stressful final day of Henry Hill before pre-police capture discloses the structural and tonal change of the film. It is here where Henry breaks yet another rule, one of which is most paramount to Jimmy: ratting out his friends, and opening his big mouth right into Witness Protection, and more importantly, court. We are now watching a completely different movie than before in the second half, indicated in the subsequent Fourth-Wall break that demonstrates the saddening and conclusive tenor.

GoodFellas is not only historically accurate, not only incredibly handled presentation wise, not only a masterpiece of a crime film, but also (for me) indisputably the best gangster, mob, Mafia, or crime thriller film of all time.

It is a thrill, that much like the film’s crime operation, is now all over, with our protagonist residing within mediocrity and nobody-hood, like us.