‘Elvis’ Review: Delightfully over the Top

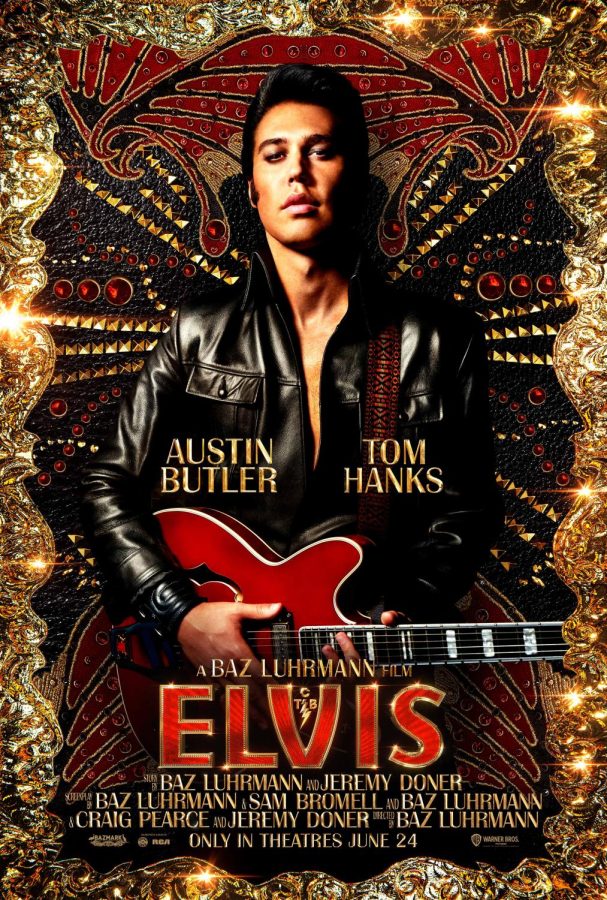

Though the 2022 film Elvis is something of a biopic about the musical icon, the film houses a story arc similar to movies made by Marvel Studios. Director Baz Luhrmann’s movie, which has amassed eight Oscar nominations including Best Picture, portrays Elvis Presley as nothing less than a superhero with magical powers over audiences, particularly women, of all ages and races. But in this case, the villain outlives the hero and the story becomes more of a Shakespearean tragedy.

From the jump, the audience is given a storybook villain in Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), the crooked, gluttonous manager of Presley. This unreliable narrator purports to tell the “true story” of Presley’s life by declaring, “Without me, there would be no Elvis Presley.” Luhrmann respects the audience to see through Parker’s self-aggrandizement by showing us his background as a shady carnie who scammed rubes, and hinting at his gambling habit (the clatter of slot machines plays faintly multiple times while he’s on screen). Buried beneath pounds of prosthetics, looking like a bloated and sun-damaged bag of skin, Hanks gives the Colonel no redeeming qualities.

Luhrmann tells the story of Presley’s life in three acts – rebel, pop artist, then the sad road to the icon’s death in 1977 at age 42. In the first act, a young Elvis ignores segregation norms and is drawn to Black musicians performing in a revival tent, which enthralls him. Luhrmann draws a line from this experience to the pop star’s first record, “That’s Alright Mama,” which we see explode in popularity. The song reaches the ears of Colonel Parker when Jimmie Rodgers Snow (Kodi Smit-McPhee), son of country singer Hank Snow (David Wenham) who is managed by Parker, plays it in hopes of inspiring Parker to sign Elvis as a new act to attract young folk to their carnival. Jimmie shocks his father and, vitally, Parker when he tells them that the future King would be performing on the radio show “Louisiana Hayride.” The radio show is recorded in Shreveport, Louisiana, where a Black singer would not be allowed to perform. Jimmie replies, stunning the other two men, “That’s the thing; he’s white.” Parker quickly becomes infatuated with Elvis’s emulation of the style of Black artists of the era. More to the point, he also smells talent he can exploit to make money.

Baz Luhrmann’s films are defined by glitz and an emphatic breathlessness in pacing that itself can feel like a carnival ride. No stranger to ambitious projects, Luhrmann has previously reinvented classics, melding the modern and traditional with his Romeo + Juliet, The Great Gatsby, and Moulin Rouge!. There is a lack of naturalism in his art; flamboyance, fantasy, and flashiness are favored over reality. That flamboyance extends to the costumes, designed by the meticulous, Academy Award-winning Catherine Martin (who also is the director’s wife). The full strength of his actors is necessary to fulfill Luhrmann’s vision for spectacle. When talking about the Elvis production, Austin Butler recalled multiple instances in which whole scenes were rewritten on the morning of shooting.

At times, the film falls into unadventurous territory – we see the epic rise in Presley’s fame, mistakes he makes along the way, and his ultimate ascent to god-like status. Tragedy strikes early when his mother, Gladys (Helen Thomson), dies. His father, Vernon (Richard Roxborough), cracks under the pressure of being the sole parent of Elvis. The simplicity of the story is drowned out by the Luhrmann-style of moviemaking. Many shots plow through any round objects the camera can find – Elvis’s eyeball zooms into a record zooms into the roof of a water silo. The raucous cinematography, directed by Mandy Walker, is now Oscar-nominated. This style works well since the film centers on a man who thrived in rhinestone-clad jumpsuits and velvet-curtained hotel penthouses.

Austin Butler’s performance as Elvis left me shaken, dazzled, and obsessed. I don’t know if I’m incredibly biased, or if I just consumed the movie the way we were supposed to, but I would love to see him win his Oscar nomination for Best Actor – he’s already won his first Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Drama Motion Picture. Inevitably, Butler was tasked with the chore of oozing sexiness. He does. To keep up with Luhrmann’s script, the replication of The King’s mannerisms and voice had to be perfect. Butler has previously appeared on many teen shows, including Zoey 101, iCarly, The Carrie Diaries. He also appeared on Broadway in The Iceman Cometh, and in Quentin Tarantino’s film Once Upon A Time in Hollywood. We should be grateful for Butler’s clairvoyant former girlfriend, actress Vanessa Hudgens, for inspiring him to pursue this role. He smothered himself in Presley content to portray the icon. It paid off; he is uncannily accurate throughout the film.

The real-life Presley, while much acclaimed during his life, also has been criticized for appropriating Black music and profiting from it to an extent that Black artists, the rightful creators, could not. There is merit to that view, and the issue is complex. It is worth noting that one of Elvis Presley’s defenders was his fellow Mississippian, blues artist B.B. King, who said, “Music is owned by the whole universe. It isn’t exclusive to the Black man or the White man or any other color” (quoted in the Vanity Fair June 24, 2022 issue). The film does not take sides on the argument about appropriation; however, it does show the influence of Black artists on Elvis’s musical style. On the other hand, though the film does show deep gratitude for Black music and artists of the era, at times, it could be interpreted to imply that Elvis unearthed these pioneers rather than appropriating their work and popularizing the style among White audiences.

The film does attempt to depict the racial dynamics of the country at the time Presley was alive, but not significantly enough. Cutaways to “Whites Only” signs, for example, don’t suffice. The complexity of the issue is shown at different levels of intensity. In one scene, B.B. King (Kelvin Harrison Jr.), the American blues artist, bluntly explains to a young, oblivious Elvis the privilege he has to be White and perform in the style he does, “They might put me in jail for walking across the street but you a famous White boy.” The racial tension that gripped America during this period is displayed simply as a backdrop in the film.

Elvis is a superhero every time he swerves away from the expectations of the entertainment industry. Elvis is a superhero every time he causes throngs of people to become possessed by his rebellious and suave demeanor – a simple swivel of his hips prompts the men in the audience to yell for the women they accompany to get a grip. Elvis is a superhero when he uses his Spidey-Sense to detect an anti-integration, pro-white supremacy meeting across town before performing in front of Black and White fans.

It’s hard and ambitious to try to condense a life, especially that of a person who was known to many as The King. It’s impossible to understand the level of Presley’s fame, which could not be repeated today for a variety of reasons. Luhrmann’s choices that made this movie less of a list of events and more of a collection of American culture from the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s work exceedingly well. Elvis Presley’s zigzagging, panting, sweaty, edgy, young, lonesome, raw, homegrown spirit has been rendered masterfully by Butler and amplified by a heavy dose of Luhrmann sensationalism.

Amy Calder • Feb 1, 2023 at 11:29 pm

Your review prompts me to want to see this film!