The Key to Success in High School: Starting School Later

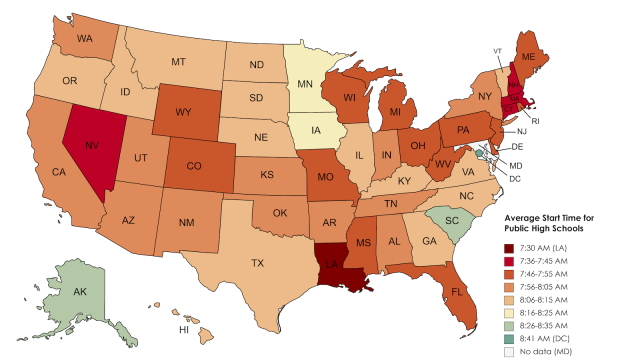

The majority of schools across the US start before 8:00, with especially early times in New England.

March 2019. I’m in fifth grade. I wake up at 6:45 am every day, charged by constant little kid energy and a bedtime of 8:30 pm. I take my time picking out my clothes before sitting down for breakfast with my mom. Being a pretentious child, I spend the hour after that watching last night’s episode of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Once that’s done, I have another 15 minutes before I stroll out to my bus stop for 8:45. This was my relaxing morning routine for several years of my life.

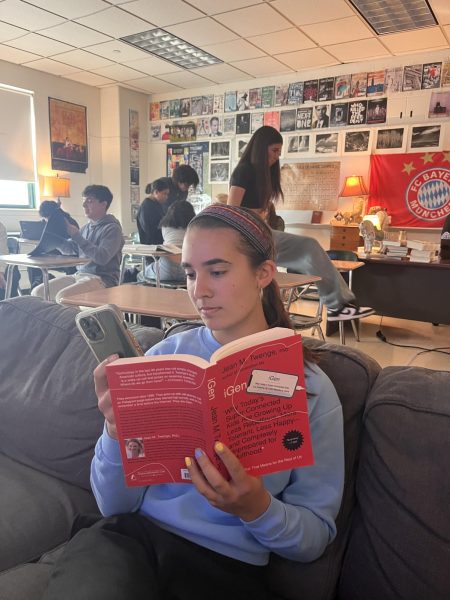

March 2023. I’m in ninth grade. I wake up at 6:00 every day, sluggish from a sleep issue I’ve had since sixth grade and a bedtime of 10:45. (No matter how much I try to discipline myself, I get a shot of energy late in the evening and can’t find it in me to head to bed at a reasonable time.) I race downstairs to make breakfast, which I eat upstairs as I throw on the clothes I picked out last night. I have 45 minutes to complete all the bare necessities of getting ready for the day – nothing more. My best friend texts me at 6:30; she’s the first stop on our route, and she missed our bus that picks her up at 6:28. She drives over here to meet me at my stop while it’s still dark out. It’s a good day, so I’ve tied my shoes before I run out the door. I trudge onto the bus at 6:50, carrying a fatigue that will weigh me down for the entire day.

Is it any wonder that my sleep difficulties began in middle school? I, like so many other teenagers, am a victim of early school start times.

Every year the CDC releases a new study that comes to the same conclusion: teenagers’ unhealthiness, low energy, mental health issues, risky behaviors, and poor grades are due to school starting too early to provide them with the amount of sleep necessary for a human to properly function. Yet year after year, nothing changes. The American Academy of Pediatrics advises secondary schools to start at 8:30 or later. Five out of six secondary schools, including Dartmouth Middle and High, still start before 8:30.

Society has accepted that perpetual exhaustion is simply part of the teenage experience. However, listening to science and daring to break the broken structure districts have clung to for so many years can change that norm.

Later Times Benefit Everyone

Obviously a good night’s sleep is key to a healthy lifestyle, but a teenager’s sleep cycle is biologically different from a child’s or an adult’s. Every organism has a circadian rhythm, a natural process that controls the sleep cycle. According to the non-profit Start School Later, “the hormones that regulate sleep make it difficult for a typical teenager to fall asleep until after 11 pm and to wake up and be alert before around 8 am. Making them get up as early as 5:30 a.m. to catch the bus – right when they are in the deepest part of their sleep cycle – robs them of the deep sleep they need to grow and learn.”

On top of that, teenagers – and most adults – need eight to ten hours of sleep to wake up in their best health, mood, and preparation for the day. Across the nation, teenagers sleep for seven and a half hours a night on average, with several Massachusetts schools finding that around half of the student population gets six or less hours.

What does eight hours of sleep look like? Improved academic performances.

The National Education Association (NEA) cites a 2018 study done in two of Seattle’s public schools, focusing on a particular biology course. Their start times were pushed back almost an hour, allowing for an average of 34 extra minutes of sleep. “Among students whose start times were delayed,” the NEA reports, “final grades were 4.5 percent higher, compared with students who took the class when school started earlier.”

With academic improvement in mind, later times also have the potential to close district achievement gaps. Sarah C. Fuller, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, co-authored a study by the American Educational Research Association on the effects of elementary schools with reversed times. She concluded that “traditionally disadvantaged groups may benefit most from supports that schools and districts can provide to address disruptions in childcare and transportation created by a change in start times.”

Since the argument of later start times is mainly based around students’ health, it can be easy to overlook teachers’ roles in this change. The NEA examined a 2022 research article, which discovered that “later secondary school start times is a significant policy shift that not only improves the health and well-being of adolescents, but can also equalize healthy sleep duration for all K-12 teachers.” The researchers followed secondary school teachers in a Colorado district after the high school start time was pushed back 70 minutes and the middle school’s around 50 minutes later. Three years after this change, teachers felt “less stressed and more rested.” The same study found that giving elementary schools the earlier start time had no “ill effects” on their learning or the health of their teachers.

Ending the Disruption of Sleep Could Disrupt Schedules

When researching counter arguments for this piece, it was difficult to find claims that had any substantial supporting evidence. Together, a thread of tradition weaves between them, the frets of people who don’t want to change what has always been routine. However, if traditions are causing the problem, shouldn’t traditions change?

A common complaint was that club meetings, sports practices, and after school jobs would have to begin later, thus limiting the amount of time students have at home before bedtime. Having more energy to begin the day with would make students perform better in sports, while still having some leftover in the tank for any homework afterwards. If they don’t complete it all, they still have an extra hour in the morning to finish; if they do complete it all and it’s quite late at night, they still have an extra hour to sleep.

The greatest concern, however, is how this will affect transportation. Parents who base their mornings around dropping their children off at a certain time before work now have to make their busy schedule fit this new mold. Although this argument is presented as large and looming, it would die down as the transition eventually became their new routine. If a family moved into a town with a different start time, they wouldn’t decide to pack their bags and find a new place again. Even if it’s difficult at first, they’d find ways to adjust.

If individual transportation becomes too challenging for parents to conquer, they can always turn to the bus. In the world of supporting early start times, it seems buses don’t exist. While having more students take the bus is the greener option, it’s also less time consuming to drop off a child at their stop rather than drive them all the way to school. Taking the bus ensures both the child and the parent can make it to school and work on time.

What a Later DHS Could Look Like

Making start times later isn’t a faraway phenomenon; it’s happening right in our state. Along with a page that tackles fallacies about pushing back start times, Start School Later shows off a list of districts across the nation who begin school no earlier than 8:00. In Massachusetts, 27 secondary schools have altered their schedules. Kinks such as finding before school care still need to be smoothed out in some towns, but, as with all changes, there must be discomfort and adjustments before progress reveals itself.

There seems to be an overall trend linking the towns that make the change: childcare, sports, clubs, and jobs shift along with the school. So much of a community’s present and future state relies on its children, so it makes sense and is a worthwhile impact to build a community based around school.

One of DHS administration’s biggest obstacles is the amount of tardies that wash over the school year. Instead of being an ineffective, novel reprimand during the Spirit Week pep rally, tardies can become a thing of the past. The motivation to go to school skyrockets among students when they have the proper health and drive to get an education. Early start times nourish burnout.

For a school like Dartmouth, whose rampant and competitive perfectionism demands students overachieve, it’s counterproductive to expect excellence while stripping students of sleep. So, in the face of overwhelming evidence, why haven’t we just made the change?

While there are of course logistical challenges to pushing back start times, several school districts have already proved they aren’t impossible hills to climb. They have come out successful with an improved student body academically, physically, emotionally, and mentally. Overall, the reason more schools haven’t made the switch is one of fear. Fear of challenges, fear of parent pushback, fear of change. That fear trumps greater academic success among a more engaged student body. That fear trumps students’ physical and mental well-being. That fear trumps the district’s ability to make the right decision.