Saving Lives or Saving Face: The New Allergy Policy

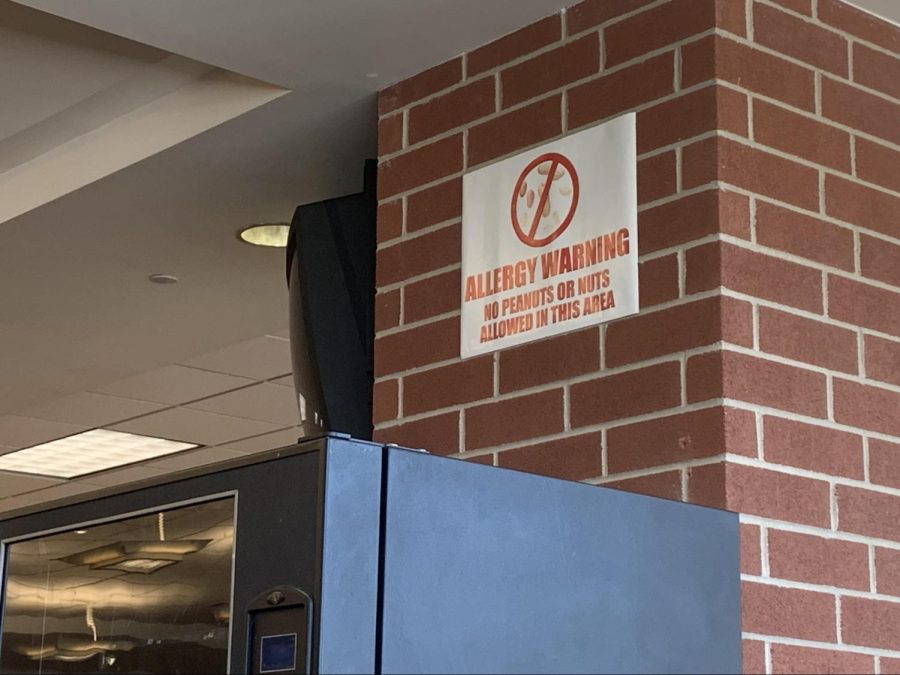

The DHS Cafeteria: No peanuts or nuts allowed in this area.

The new allergy policy has been another unprecedented change in DHS, but with the change comes more questions than answers. In fact, as the phone policy made waves outside the DHS community, the allergy policy seems to have warranted more of a reaction from students and teachers.

The new allergy policy is the prohibition of all outside foods and affects classroom parties, snacks, food delivery services, and outside drinks such as Dunkin’. This policy is in direct response to an anaphylaxis attack that a student experienced during an elementary school party in which food was distributed. It is unanimously recognized that this incident was an avoidable accident, and an unfortunate precedent for such changes to the allergy policy.

That aside, discrepancy in opinion about the allergy policy starts with how it should be applied to different ages. After all, rules and policies vary from school level, and it would be bizarre for an elementary student to be penalized for academic integrity, just as it would be futile to take away coloring time for a high school student who was late.

At its core, the new policy is a safety precaution. “It’s important that everyone is aware of the dangers of allergies. Having these new policies is bringing to light the importance of the safety of students,” said DHS Nurse Marisha Wildrick.

However, it would be misleading to say that DHS was in dire need of a policy change considering what Mrs. Wildric also said. “We don’t usually have a lot of allergy reactions because everybody here in this school, even before these policies were implemented, did a really good job,” she said. This makes sense as according to Mayo Clinic, half of children with allergies grow out of them, food allergies affect 8% of children and only 4% of adults, usually growing out of such allergies around 16 years old.

The biggest argument against the policy is that the cafeteria has been designated as the only place for food in DHS, in fact it is counterintuitive. The “allergy aware zone” can serve allergens such as eggs, one of the most common, but classrooms can’t have less common allergens such as sugar candy? The logic behind this is to have students in an area that is clean of trace allergens.

However, according to the Food Allergy Research & Education non-profit organization, severe reactions come primarily from ingestion. Deaths from airborne allergies, according to Greater Austin Allergy, is extremely rare, and is more common to happen when food is being cooked, or the allergen is of the powder variety, and when ventilation is poor. From that perspective, policy or no policy, as long as a student with allergies doesn’t ingest what they are allergic to, even if others are eating it, a severe reaction shouldn’t occur. It is simple science: a reaction is caused by the introduction of the allergy to the immune system. No introduction, no reaction. By high school, it is expected that people with allergies know to avoid those foods, so the new policy is excessive, and unnecessary to the avoidance of allergy attacks. Most students aren’t cooking soy-powdered fish in psychology class.

However, other types of students have been suffering. Students who haven’t eaten breakfast, have low blood sugar, or are just plain hungry now can’t eat without going to the nurse’s office. Instead of just popping a couple of M&Ms and continuing on in class, students have to waste time by leaving the class to refuel when they could be learning.

It is also a safety concern. If a student is so hungry they are feeling faint, isn’t it more of a risk to travel, sometimes multiple flights of stairs, to get to the nurse? Consider this scenario: A student on the C-floor with low blood sugar is starting to feel faint, and they ask to go to the nurse to get a snack. Traveling down the stairs the student falls down the stairs, potentially causing serious injuries. Grievous hospital bills and physical trauma could have been avoided if the new policy allowed for the eating of at least some foods in the class. No doubt, most common allergens should be prohibited in the classroom, but aside from that, there is statistically little harm in alleviating the allergy policy.

The administration is reworking the allergy policy, but we only get so many tries to correct an important policy that affects so many students. “Sometimes when we have reactions, we kind of go overboard, and then pull back to what tailors to us,” said DHS principal Mr. Shea.

But who will be tailored to and how? The future of the DHS allergy policy and food policy remains obscure, but until a new policy is implemented we have no choice but to trust that the administration and allergy committee will do what’s best for its students.